Biography

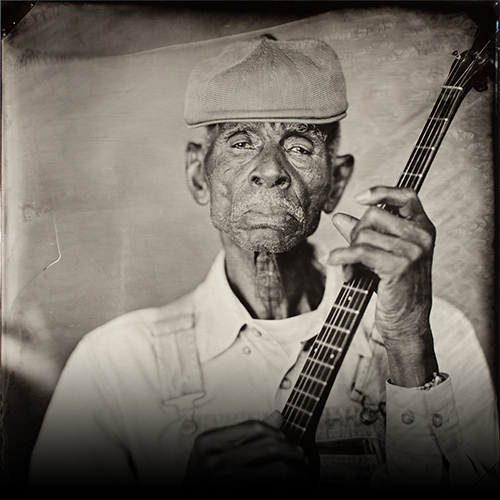

Chicago has always been the epicenter of much of the world’s greatest electric blues, but its satellite cities with substantial African American populations also boast underground scenes that offer amazing musical discoveries when some searching is done. Among the hidden gems blues fans will find in Racine, Wisconsin, is veteran guitarist/singer Pee Wee Hayes.

How We Helped:

Music Maker Relief Foundation has given Pee Wee a brand new guitar and has been helping him with career development.

“I Just Ain’t Had an Opportunity”

by – Steve Sharp

Chicago has always been the epicenter of much of the world’s greatest electric blues, but its satellite cities with substantial African American populations also boast underground scenes that offer amazing musical discoveries when some searching is done. Among the hidden gems blues fans will find in Racine, Wisconsin, is veteran guitarist/singer Pee Wee Hayes.

Although he lives 50 miles north of Chicago, Hayes is an artist one might easily mistake for coming straight out of the Windy City. His burnished, deeply soulful voice and hard-edged, stinging guitar are reminiscent of B.B. and Albert King and sound as if they could be emanating from the door of some South Side tavern circa 1965. The truth is, however, Hayes was never a big part of the Chicago scene. He eschewed it, in fact, doing his own thing in the road houses of Wisconsin and northern Illinois.

The story of the lone wolf Thomas O. “Pee Wee” Hayes is a sometimes chilling tale of childhood myths and fantasy that Hayes tells with dramatic flair and humor. Hayes’ laughs punctuate even the most harrowing parts of his autobiography, which comes replete with the near-lynching of his father, as well as his gun-toting antics as a child.

Born July 13, 1944, in Alamo, Tennessee, northeast of Memphis, Hayes was the third oldest of seven boys and three girls. The nickname “Pee Wee” borders on the ridiculous when one considers Hayes’ substantial height and middle linebacker–like physique.

“Pee Wee was the nickname my family gave me when I was a little boy,” Hayes told LB. “It stuck with me ever since. My dad always gave all of us nicknames—Pee Wee, Hog, stuff like that, you know.”

Hayes’ childhood was short on formal education but long on myth and superstition. One tale of his youth has him chasing a figment of his imagination through the fields adjacent to his family’s home with a double-barreled shotgun at age four.

“When you is a kid, you had fantasies in the South, man. You go by what you hear about the Gingerbread Man, Little Black Sambo, Brother Rabbit and Brother Fox. They thrives off of that stuff for tellin’ bed-time stories. When I was a little boy, I was told that the Gingerbread Man, the faster he runs the more bread he leaves behind. So me and my brother discussed it and Mom, she was out workin’ in the fields, choppin’ cotton, pickin’ cotton, strawberries, anything to make a livin’ for the kids. My dad, he was like one of these Superfly characters back in the days. He was there and sometimes he wasn’t. He had a woman on the side. So we had to get together and try to help feed each other. So me and my brother, we said, ‘If we catch that damn Gingerbread Man, we ain’t gotta worry about somethin’ to eat. We’ll have somethin’ to eat.’ So my grandmother, she had a few guns in the house and we would sneak through the back door—sneak a gun out of the house and lay in the field and wait on the Gingerbread Man. We could smell somebody cookin’ somethin’ sweet, you could smell it all over town. We said, ‘Oh, the Gingerbread Man is around here somewhere!’ We could smell him! So we were gonna get that son of a bitch! And I remember an old calf came through the field and it was kind of dark outside and we saw the white face and we said, ‘There he is!’ We knew the Gingerbread Man had big white lips and big white eyes, and we saw a white-face calf comin’ through the field and we shot it. The man who owned the cow whipped us and then our parents whipped us. We killed a man’s calf and we got one of the worst ass-whippins we ever had in our life!”

Hayes’ childhood was filled with mischief. “As I was comin’ up, man, we got in all kind of trouble. What the average kid would get into, livin’ the kind life we lived—especially in the South—it was rough down there. Almost everybody was livin’ in poverty—not only blacks. Those who ‘had’ lived good and those who ‘didn’t have’ lived bad. They lived the worst.”

Hayes’ grandfather was a preacher and although Baptist church music was a presence in his life, Hayes grew up listening to blues. “Mostly what I heard was blues music on the radio. They had them old dry-cell radios and you had Randy’s Record Shop, Randy’s Record Mart, and all that stuff. My dad, he had to have his music everywhere. He’d take his radio—one of those big radios—out to the field when he was workin’ or plowin’ or somethin’ and tie it to his tractor, or he’d set it somewhere and when I’m out in the field walkin’ behind the tractor or ridin’ with him on the tractor I would listen to the blues.”

Hayes’ early recollections of blues include hearing Sonny Boy Williamson I on the radio. He also listened frequently to Sleepy John Estes, Yank Rachell, Hammie Nixon, Washboard Sam, and others. Hayes’ father owned a cafe that was another source of blues inspiration to him.

“A lot of musicians, like B.B. King, traveled on down through there and played. Another guy had a cafe right across from dad. My dad was always receiving threats because my dad was a musician and he always brought musicians down into that area. So he was receiving threats that his cafe was going to be dynamited if he didn’t close up. The other people didn’t want the competition. See, my dad didn’t want to pay undercover either and the sheriff wanted to get paid undercover. So the KKK threatened to blow up his cafe—they was talkin’ about blowin’ the whole corner up, but this other guy with a cafe he paid him—he paid up—but my dad didn’t want to, because he didn’t think it was right.”

Hayes said he grew up “pretty quick” but still recalls the significant event of being given a toy guitar at the age of two and a half years old. The toy whetted his appetite for becoming a musician.

“After that I had to sneak and play my father’s guitar. He was a bluesman, one of the best around in the area. He played juke joints, house parties, backyard parties, everything. I remember my dad always hid his guitar—I never could find that doggone guitar. He didn’t want any of his kids messin’ with it. So after the little toy guitar, me and my brother got into some kind of little misunderstanding and he took my guitar and threw it onto the railroad tracks under the train and the train ran over it and I grabbed his banjo and threw it out there under the train and we didn’t get guitars for a long time, until we got older. So we tried to find our dad’s guitar and sit around and strum on it.”

Hayes hinted at the paranormal when recalling the time he was able to finally locate his father’s guitar. “I don’t want to go into detail because this was a strange occurrence, you know, but I can give you a little bit of it. For some strange reason, man, I was in the bedroom and I was playing with some little paper horses tied to a matchbox and I saw a cat come in the house. My grandma had a little place cut in the door where the cats could come in and out. I never seen this cat before. He was walkin’ through the house and he went under the bed. I would see cats every day, but a big black one, I never saw one that big. I said, ‘Damn, that’s a big black cat.’ And all of a sudden I heard notes being played on a guitar and I said, ‘Man, what’s goin’ on?’ It was the cat under the bed, and that’s where I found the guitar. My dad had it tied to the bedsprings. So if it wasn’t for the cat I would have never found it. We looked all over for it. We even looked in the barn. We could never find that guitar, man. And when my dad would come home we’d be outside when he played the guitar on the porch and we knew he went back in the house with it, but we looked all over in the house and we couldn’t find it, so we went to our grandfather’s house and looked in the barn, and looked in the smokehouse—they had smokehouses back in those days where they’d hang hams and the other kind of meats to dry out. We searched all over for it, never could find it. But that old cat found that guitar!”

Hayes’ father began teaching him to play chords when he was six or seven years old. “He taught me to play old Jimmy Reed–type stuff, something similar to that,” he said. “But I never could catch on to it, because they would tune their guitars different in those days.”

Hayes said he moved north because he “had no choice.”

They was tryin’ to lynch my dad down there, so he came up here. He was sharecroppin’ and after he planted the fields and all that stuff, and he got ready to harvest the fields, the boss told him he couldn’t take anything out of the fields. My dad said, ‘I got kids and I have to feed my kids.’ The boss said, ‘You don’t take nothin’ out of the fields. You go back to work.’ And my dad said, ‘I’m not workin’ today. You mistreated me.’ And the guy said, ‘You go back to work.’ So my dad ran in the house—I don’t know what he went after—but he came back out with a hammer and this man had a shotgun on him. So my dad ran back in the house and ran out the back door. So the man took his truck and went home, and I guess he called his sons and stuff, and everybody got together and they organized a posse. So my dad ran down through the fields somewhere. He went out the back door and I knew there was a big river down there behind us and there had been a big storm about a week before that and the river was overflowin’. So my mom said, ‘Oh, go down there and see if you can find your dad!’ So we went down there lookin’ and we saw a big old log turnin’ over in the water. I said, ‘There he is! There he is!’ And we went back home and we reported that he was in the river, he had got drowned and he was goin’ down the river. So you know the family panicked and there was mournin’ goin’ on. So he was able to get away!”

After more acting on the part of the family, including substantial crocodile tears emitted by his mother, Hayes said his father contacted them and told them to move north with him to Racine, the industrial, harbor city he still calls home.

“I was a kid—about eight years old, but my dad came here because he knew somebody. I never knew anything about Racine. I didn’t know anything but down south. I guess they put my dad in a box or somethin’ and shipped him up north here in a crate or somethin’. I don’t know how they got him up here. I think it was a crate—he talked about it.”

Hayes started playing blues around Racine at the age of nine. “I was just playin’ in somebody’s livin’ room, playin’ outside doin’ picnics and stuff like that—just one guitar, maybe two guitars—somebody beatin’ on buckets or somethin’ like that. Then in 1958–59 I started playin’ with a band. I played there in my teens and I made good money back in those days—better money than I’m makin’ now. We did old rock ’n’ roll and blues, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and all the guys—Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis. We did all that kind of stuff. We had a [racially] mixed band. It was two black guys, a white guy, and Mexican guy. We wanted it that way, man, so we could get in them clubs. I infiltrated a lot of white clubs around here in Wisconsin. There was no blacks playing in white clubs then, see? I was thinkin’ if I got a mixed band, we could play at different clubs and that is what happened.”

Hayes recalled B.B. King was a huge influence on his style. “We grew up wanting to be like B.B. King ’cause he was out there and I knew B.B. King when I was just a young boy. He used to come to my house and eat and play at my daddy’s cafe. He played in the yard. He had a little amplifier and back in those days I wasn’t familiar with an amplifier, and he’s sittin’ out there pickin’ with an amplifier. It was the good old days. B.B. King was the greatest influence in my life. I also like Albert King and Albert Collins.

Hayes recalls encountering Jimi Hendrix “before he really started playin’ blues.” Hendrix sat in with his band at the Alibi Club in Kenosha, just south of Racine. “He was wild man,” Hayes said of Hendrix.

As a young man, Hayes jammed with Little Walter at the Hawaiian Lounge in Waukegan, Illinois, and he made occasional treks to Chicago’s South Side clubs, where he met Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy and many others. He recalls meeting Junior Wells in 1959. Hayes said, however, jealousy on the Chicago blues scene turned him off and he opted to live and perform outside the city.

“There was jealousy and animosity bullshit goin’ on in Chicago—you know, personality conflicts back in those days. I was a young guy—used to play with my teeth and all that stuff back in those days. I was just a hyper type guy and I used to just let it all hang out when I was in front of a crowd. I wasn’t really very well liked in Chicago. They were always accusing me of trying to steal their gigs, but it wasn’t like that. I just love music and I’d go over there and sit in with people—they were kind of rude to me.”

Hayes’ recordings are limited to a few informal collections he has recorded at home. He duplicates them himself when he can. Among these is The Blues Is Here to Stay, recorded in the 1990s. Hayes’ dream is to record more and become a part of the blues festival circuit. “I been holdin’ these hits back for so long. I just know I can make a hit man. You can feel it, you know?”

Hayes’ brother Charles is an outstanding bluesman in his own right. Hayes credits Charles with helping him on guitar in his formative years and the two perform together to this day. “We have a family band together. We all played together a lot of times, but I was somewhat like a leader. We play good together, man, but he has a different style than mine. I am a high-energy-type musician and always have been, and he’s more like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and different peoples. He’s got his own style, though. He’s got a very unique style. I like his style. As a matter of fact, he helped me get some of my chords, my timin’ together on the music when I was young.”

Hayes said he feels like one the blues’ unsung artists. “Blues is my thing. I just do music ’cause I love doin’ it. I just love playin’ music, man. I been at it a long time and they just won’t give me a break. When you said, ‘You want to do somethin’ in Living Blues?’ This is what I was hopin’, man, you know? ’Cause I can hold my own ground if I can get out there like I need to be. It’s a long story, man. I just ain’t had an opportunity.”