Biography

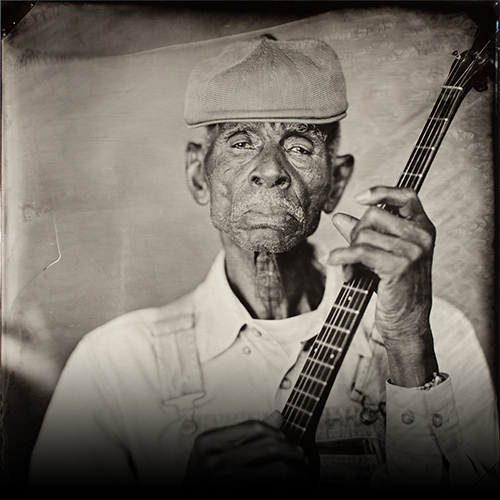

Mr. Frank Edwards, elder statesman of Atlanta’s blues community, died Friday, March 22, 2002 in Greenville, SC. He was 93.

Born March 20, 1909, in Washington, GA, Edwards left home at 14 after a disagreement with his father, bound for St. Augustine, Florida. He bought a guitar and began learning to play, receiving encouragement from guitarist Tampa Red (a.k.a. Hudson Whittaker). Later, Edwards took up harmonica, drawing inspiration from John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson and others.

How We Helped:

Music Maker Relief Foundation provided Mr. Frank Edwards with a monthly stipend for prescription medicine. He was in retirement for 10 years before Music Maker brought him out for many years of touring and performances throughout Georgia. Music Maker also helped Frank record a CD, and featured him in the book Music Makers: Portraits and Songs from the Roots of America (2004).

Edwards traveled extensively through the 1930s by bus or train, “hoboing” when he had to while he learned his trade as a street musician. He moved to Atlanta in 1936. An association with Mississippi bluesman Tommy McClennan led to Edwards’ first recording session in 1941. He recorded again in 1949 and released a full-length LP, Done Some Travelin’ (later reissued on CD) on the Trix label in 1973. He also supported himself as a carpenter, painter and plumber, but always played music, except for a two-year period when a house fire left him without a guitar.

In a career that spanned nine decades, Edwards saw blues evolve from an exclusively black folk music form into a commercial entity that was embraced by both whites and blacks. When he began playing music, “didn’t nothing like [blues] then but black [people],” Edwards said in a 1998 interview. “Didn’t none play it but black. After so many years, white folks caught the blues. Now that’s what they want to hear. They liked it all that time, but they was ashamed to listen to it, because nothing played it but black[s]. They’d just buy the records, get in the basement with a gallon of liquor, drink it and listen to the blues. I hear a heap of ‘em say it.”

Fittingly, the last months of Edwards’ life—in fact, the last hours—were spent playing the music that he loved. In fact, he’d enjoyed a relative flurry of activity, performing at the Atlanta History Center for its “Nothin’ But the Blues” series and at the Georgia Music Hall of Fame annex at Discover Mills in Lawrenceville, GA.

On the day he died, Edwards had completed a recording session with Tim Duffy. He was returning home, riding with Atlanta area blues supporters Larry Garrett and Lamar Jones, when he suffered a heart attack in Greenville, SC. He died in an ambulance en route to the hospital.

The March 22 session featured seven songs, including new, original material, with John Ferguson playing drums in support, says Tim Duffy, Music Maker’s founder. Duffy says that recording, which included two previous sessions, was complete and Music Maker had planned to “fast track” the CD and have copies in Edwards’ hands within weeks.

“He played the best I’ve ever heard him play,” Duffy says of Edwards’ last session. “He was blossoming. He had his own distinctive style that he never let go of.”

Edwards had been working on the Music Maker recording since 1995, Duffy says. Edwards initially recorded a solo session in Atlanta (you can hear his “Chicken Raid” on the recently released Blues Came to Georgia CD, issued jointly by Music Maker and the Georgia Music Hall of Fame) and had recorded in 2001 in a band setting with Danny “Mudcat” Dudeck.

Edwards expressed frustration in dealing with the recording industry, but was pleased to work with Music Maker. “Tim Duffy is a pretty fair fellow, ‘bout the straightest one I met yet,” said Edwards in 1998. “Don’t none of these record companies believe in paying nothing much. Most of them are deadbeats, cheaters and swindlers. They don’t pay nothing, but they make good money.”

Locally, however, the Atlanta blues appreciated and acknowledged Edwards’ contributions and his status in the community. On March 20, two days before his death, Edwards was the guest of honor at his annual birthday bash at the Northside Tavern. Organized by Danny “Mudcat” Dudeck, the party featured performances by many local blues musicians, including Cora Mae Bryant, Eddie Tigner, Carlos Capote, Ross Pead, Donnie McCormick and others. The evening concluded with Edwards playing for roughly an hour, backed by Jim Ransone on guitar, Dave Roth on bass and Evan Frayer on drums.

“He was strong, the strongest I’ve ever seen him [play],” Dudeck says. “Ever since I’ve known him, he’s just gotten better and better. But he was on fire [that night], and I’m not the only one to say that… He went out at the top of his game, with brand new songs, with fire, with a big party. He knew he was loved.”

Adds guitarist Ransone: “Mr. Frank was such a total inspiration to still be going at it at 93. It was inspiring how much he loved music.”

Cora Mae Bryant, daughter of longtime Piedmont blues musician Curley Weaver, recalls Edwards performing with her father and uncle around Conyers and Covington in the 1940s and ‘50s. “They would play at barbecues and fish fries, play at people’s houses. We used to party, get [dressed] sharp and get on out with the music.

“We used to call him Mr. Cleanhead,” Bryant says fondly, referring to Edwards’ lack of hair. “We loved Mr. Frank’s music.”

When not performing, Edwards was a regular at local clubs, appearing virtually every night at Blind Willie’s, the Northside Tavern, or other venues.

Vocalist Francine Reed remembers: “He was a good friend. I love him and I’m going to miss him. [But] his spirit will always be with us, of that there is no doubt.”

For blues bandleader Beverly Watkins, Edwards was “beyond an artist. I’d say he was a minister in music.”

Watkins also says that Edwards was “like a father to me. My dad died about four years ago, and I could go up to [Mr. Frank] and tell him a little something that wasn’t going right in my life, and he’d listen and give me some ideas. That made me feel real good.”

Such was typical of Edwards. His approach to life was to “do right by people,” Dudeck says. “Any time anybody asked him about his success or his longevity, he said, ‘You’ve just got to treat people right.’”

– © 2002 Bryan Powell