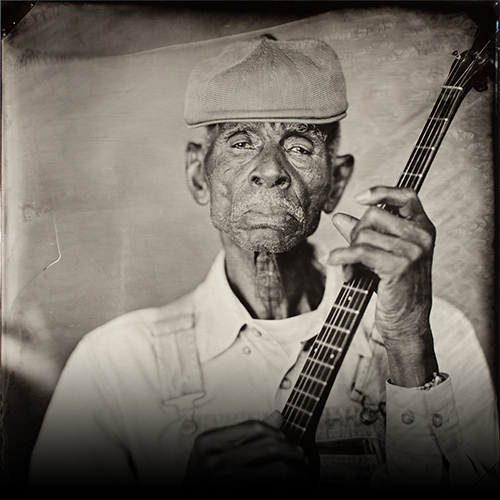

Biography

Grandfatherly Carl Rutherford’s devastating take on “The Old Rugged Cross” and other jewels showcases his unique blend of Buck Owens-style twang, old time gospel number and harrowing mining songs, making him a true American original. – CD Baby Reviews

How We Helped:

Carl Rutherford, who has been part of the Music Maker family since 1995, has received sustenance grants and emergency relief grants from the organization. Music Maker issued his recording Turn Off The Fear and featured Carl on several compilation CDs, as well as in the book Music Makers: Portraits and Songs from the Roots of America (2004). Through Music Maker, Carl has had the opportunity to play at the Portsmouth Blues Festival in New Hampshire, the National Guitar Festival in North Carolina, and at Ferrum Blues Week in West Virginia. Upon Carl’s death, Music Maker arranged for his body to be donated to the Duke University Medical School.

It’s a gray world and no yellow line, snow falling harder now. The road to Mayberry twists slick and mean once Winston-Salem recedes in the rear view. There is no Mayberry, of course. It’s really Mount Airy. Mount Pilot, also of Andy Griffith Show fame, is really Pilot Mountain, and you can see it from the exit to Pinnacle, North Carolina. On a clear day, that is, you can see it. This is not a clear day.

The slow ride leads to a steep drive, and there at the top is Carl Rutherford’s van, cased in ice, cold clothes strewn all over the interior. Next to the van is a cabin, and inside the cabin are three men, two with guitars and one without.

Carl Rutherford (1929-2006) is sitting on a chair, holding one of the guitars. He’s wearing layers of flannel underneath quilted polyester. Just now he reaches underneath his chair, rooting around in his bucket of medicine in search of something he says is a nebulizer, coughing. A nebulizer blows compressed air, turning Carl’s medication into a fog to inhale.

“It’s breathin’ treatment,” he says. “Gettin’ some of that shit out of my lungs.”

That’s the shit that he says is going to kill him, and he figures it’ll happen before too long. This is Carl Rutherford’s last recording session, so far as he can tell. He’s moving to California to be with his daughter. Moving to California to get out of the cold. And to die.

Carl used to live in California, but he’s from War. He pronounces some words sort of like Loretta Lynn does, even though she’s from Kentucky. War is West Virginia, you know. He knows about coal mining, and about organizing workers. He knows how to praise God, and he knows about things that happen “somewhere in some dingy barroom, where the lure of the gayness takes the place of our dream.” He’s known all of this for a long time.

“God stacked War just as steep as it could be stacked,” he says. “You try to do anything with that land, you’re going to have trouble. They’re little spike hills. Stick up like spikes.”

He has all these songs, Carl does. Hank Williams would be proud to sing some of these songs. “Love Can’t Fly On Broken Wings.” Hank would have liked that one. “Flyin’ High, Walkin’ Tall,” too.

Then there are the ones about the mines. “You’ve got to turn off the fear, when you come down into here,” he sings, and that’s when you know he never turned it off. Carl Rutherford saw bad things happen down there: “A man’s life ain’t nothin’/ Lordy, that’s how it seems.” That’s War he’s talking about. “You gotta pray that the dear Lord is holding you near.”

That’s for real, from a man who went to a week of funerals after a catastrophic mining accident. After that, the cage man got pissed off when Carl held up the coal show by vacillating, going back and forth about whether or not he could go back down into the mines.

“Finally, my dad said, ‘If you don’t go now, you’ll probably never go in again.’ We’d just bought a strip of land, so I said, ‘I need to stay and work and help pay that off.’ I made $16 a day. When I got the money saved, I was gone. I went to California.”

These songs, this life – lived mostly in West Virginia and California, in coal and in timber and in music – are swirling around inside the cabin like the snow swirls outside of it. Warmer than the cold is cold. John Ferguson sits next to one wall, listening to Carl, smiling sometimes, playing along. Ferguson is world class. “I don’t believe I’ve ever heard nobody any better than this fella,” Carl says. “God, he plays so pretty.” Taj Mahal says the same sort of stuff about Ferguson. Carl doesn’t know much about Taj Mahal.

“I was at a state gathering in West Virginia, and somebody said, ‘Carl, make a blues tape,’” he remembers. “I said, ‘What is blues?’ They said, ‘Carl, you are blues.’ I said, ‘Okay, then I can do that.”

Not so much gets done today. The bass player shows up, then leaves, scared that the snow will keep him from getting to Asheville in time for a paying gig.

“All the rest of ‘em were panicking with that snow,” Carl says later on. “I don’t mind the snow. It’s the accumulation that gets me.” That’s a saying of Carl’s.

Little spurts of brilliance, marred by out-of-tune guitars, recording glitches or harmony singers who can’t sing loud enough. That’s what happens today. But the little spurts are something else, man. Something else.

The whole country’s tuning up to see the Rams beat the Titans in the Super Bowl on Sunday, and the real show is in these snowy hills, north of the Super Bowl, east of War. It’s just a damned old cabin, but the little spurts are something else.

That’s not what’s on Carl’s record, though. That’s all unofficial.

The record is for the good stuff. It’s not the Last Session (which may in fact not be the last session, good Lord willing), but the one before it, recorded in the same place. The same people were there before, except for Abe. Abe is the great Abraham Reid, the skinny, bad-ass harp player who got in a horrible car crack-up between playing on this record and playing on the Last Session.

“Abe got hurt real bad,” Carl says. “He played great, and then he got hurt.” Country music is full of stories like that. Hank Garland played great, then he got hurt. Abe’s a blues man, though, and he’s probably going to rally like Garland never did. The blues is a hard life, but it’s a resilient one. Cursed and prayerful, that’s what most bluesmen are. The prayers are softer than the blues.

Ferguson is all over Carl’s album. Listen to what they played together. “I will cling to the old rugged cross,” Carl sang. You could hear Carl breathe when he’s not singing. Carl breathes loud. Ferguson set notes on top of each other, building little pyramids of vibrato, little stepping stones to something once out of reach. “I will cling to the old rugged cross,” Carl sang, and that’s clinging for real. “And I’ll exchange it someday for a crown.” That’s hope and belief, which is all we’ve got, unless you count this life.

True life hillbilly blues and mountain gospel. Little shards of California honky-tonk.

“Ain’t that something? One pass,” Carl said after he and Ferguson finished up with one of these.

One pass, that’s all.

Ferguson got it all. Carl sang “Long Black Limousine” and Ferguson copped a little piece of “Green, Green Grass of Home.” That’s understanding.

If you want to know who Carl Rutherford is, you can listen to Carl’s album. If you want to know where he’s been and what he’s done, you’re going to have to ask around West Virginia and California and Tennessee and all the other places where he’s said or sung something that moved people to feel and act differently than they did before.

Carl, you see, is somebody entirely different. He’s steeped in folklore, in mystery, in coal dust and rallies and jukeboxes.

He thinks he knows the deal with “In the Pines.” He knows about the fellow who wrote it.

“My dad knew all that, from where he grew up,” he said. “It’s about what they call The Pines, outside of Caryville, Tennessee. Out from Knoxville. “In the Pines” was two deaf mutes. She’s a gorgeous thing, and they got to courtin’. He worked on a section gang. There was a wreck down the line somewhere, and the train’s running way late. Real long sucker. She was going to the post office, and didn’t know the train was running late. He was waving at her, and it didn’t do any good. It hit her.

“Then he went crazy. Went off into the caves there that they called The Pines. About two years later, somebody found his bones in the cave. The poems he wrote was beside of him. Then there was a medicine man come through that picked the banjo and sold the black draught. Somebody gave him the poem, the words, and he set the melody to it.”

Carl sang better in the shadow of Pilot Mountain than he’d sung in years. The reflux was under control (“I found a doctor in West Virginia who knew how to control that stuff. I was sounding like Louis Armstrong before that.”). His supporting cast was up to the task at hand, and the task at hand was getting Carl’s songs down right.

That meant creating the soundtrack to a real American life. These coal-mining songs are a lot like these love songs. Shit, love is coal mining. Bad love, at least. Crunched down into a dark, fearful place, breathing in the shit that’s gonna kill you. Good love is different, but it’s harder to happen upon. And none of it matters if the Bible is for real. That’s where the clinging comes in.

“One time I was listening to me, and I almost heard a preacher, you know?” Carl said. “I almost heard a preacher singing.”

– Peter Cooper, Nashville, Tennessee, December 2000