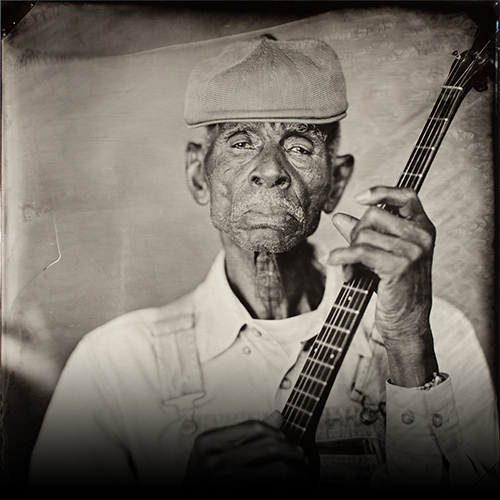

Biography

Drink houses in Winston-Salem, North Carolina’s black community, like juke joints in the Mississippi Delta, remain a vigorous setting for the perpetuation of the blues at its most real and rooted level. A refuge for the homeless and the down-and-out, as well as a gathering place for friends and lovers, the drink houses are on-going house parties where emotions run high, alcohol flows heavy, and the music is raw and from the heart. It is out of this blues milieu that Guitar Gabriel has recently reemerged to join another blues scene—the blues world that includes recording contracts, write-ups in magazines, and gigs in college-town bars and at festivals overseas.

How We Helped:

Music Maker Relief Foundation helped Guitar Gabriel obtain a passport, and provided him with grants for medicine, food, clothes, and utility bills. Music Maker has recorded three albums for Guitar Gabriel, and organized his tours in Holland, France, Switzerland, and throughout the U.S., including performances at the Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall. He is featured in the book Music Makers: Portraits and Songs from the Roots of America (2004).

Gabriel, who was born Robert Lewis Jones, has been a part of that world before. He is familiar to many blues fans as Nyles Jones, the name under which he recorded a highly acclaimed LP, My South, My Blues, for the Gemini label in 1970. The album was reissued in 1988 on the French label, Jambalaya, as Nyles Jones, the Welfare Blues. Mike Leadbitter, writing in Blues Unlimited in 1970, called the single, Welfare Blues, the most important 45 released that year. After seeing no compensation for his efforts, however, Gabriel became disillusioned with the blues scene and returned to Winston-Salem, playing occasionally with gospel groups, as well as in the drink houses.

Gabriel was born in Atlanta on October 12, 1925, moving to Winston-Salem at age five. His father, Sonny Jones (also known, apparently, as Jack Jones, James Johnson, and as Razorblade for an act in which he ate razor blades, mason jars, and light bulbs) recorded for Vocalion in 1939 in Memphis, accompanied by Sonny Terry and Oh Red (George Washington). Sonny Jones also recorded a single for the Orchid label in Baltimore in 1961 (as Sunny Jones).

Guitar Gabriel began hoboing and traveling in his teens and, with a break for service in the Army during World War II, spent his years up until the 1970s largely on the road, with stints working for carnivals and minstrel shows, as well as backing up at one time or another, according to his claims, many of the biggest names in blues through the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s. His recent return to active performing outside Winston-Salem is due largely to folklorist and musician Timothy Duffy, who located Gabriel in 1991, after hearing about him from the late Greensboro, North Carolina, bluesman James “Guitar Slim” Stephens. With Duffy accompanying him as second guitarist on acoustic sets and as a member of his band, Brothers in the Kitchen, Gabriel has been performing frequently at clubs and festivals, and appeared overseas for the first time at Blues Estafette in Holland in November, 1991. Gabriel and Brothers in the Kitchen have also issued a well-received cassette, Do You Know What It Means to Have a Friend?, on their own Karibu label.

While Guitar Gabriel’s story is, in many respects, that of the quintessential bluesman, his personality is, at the same time, quite distinctive—reflected in his outrageous headgear, his eloquent ability to express the relationship between his life and his music, and, most especially, in the music itself. Gabriel’s repertoire includes an eclectic mixture of Piedmont, Chicago, Texas, and gospel numbers—all done, however, in his own gritty, Piedmont-rooted style that he refers to as toot blues. It is a sound rooted in hard living and nurtured in the drink houses of Winston-Salem, and while Gabriel now leaves his old neighborhoods to play a wide variety of venues, his music has lost none of the emotional edge and the raw intensity needed to carry it over in its home environment, where the blues is still lived every day of the year.

– David Nelson

When I was six or seven years old I used to play with my grandfather. He played banjo, songs like John Henry, different old songs. He used to play a jug, like a gallon jug, a glass jug, he played the blues on that. He died when I was about 15.

My father used to play, he used to play for those fish fries, but I was too young to go. I’d go peep in the window. They had those set dances and stuff. He had a little band, had a bass fiddle, guitar, drums. He’d go to house parties, fish fries, chitlin struts. Me and my sister would walk down to the field and sneak up through the woods and see them dancing. But I could not go in there. I was too young for that. But I wanted to go in there so bad it was pitiful. So, that is what made me want to play guitar. [Then] daddy quit farming, sharecropping, and moved to the city. He started working at the factory at Reynolds [R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company in Winston-Salem, North Carolina]. And I wanted to play a guitar so I started messing with the guitar every day when I came from school. I’d get a whippin’—mamma whipped me—but she found out that it would do no good. I used to go to sleep with it on my chest, you know, when I’d take my nap.

My father played all the Blind Boy Fuller tunes and then he played his own stuff. He made a record, about “She’s a cold blooded murderer but she won’t matter anyway, woman that’s hard you are going to be sorry some day. He recorded as Jack Jones, but his real name was James Johnson. He made that record. . . a friend of my mother’s took my daddy away from her and they went to Detroit and I saw my father one time after that. And then I started traveling and the next time I heard. . . they said my father was dead. “I done got tired and I want to lay down and rest—that is a song he used to sing. He used to get in the backyard and sing that and mamma would cry. He would be about half drunk off of that moonshine. He’d get in the backyard with his acoustic. He could sing too. I used to jam with him a little bit, but I was very young.

I always wanted to do what I seen him do. I wanted to be a musician all of my life. So I followed him, you know. I followed in his footsteps and he showed me a lot of shit. He taught me a whole lot of shit. He said, “Son, I don’t care where you go, don’t copy behind nobody else. You can make your own stuff, that’s what makes you good. When you got your own shit, then nobody can steal it. They can come close but they can’t take it. I have a different sound than anybody. Just like the record company told me that beat me out of all that money. They said, “You got something, you got a different sound than all these other musicians.

I was never satisfied in one place. I wanted to learn about other people and the way they were living in other parts of the country. You see if you live here and never go as far as the corner store for 20 years you will never know what anything else is like. It is good to keep moving—you learn like that.

The first place I went was to my grandmother’s in Atlanta, Georgia. I stayed down there a while. I got better and better and I said—shit—let me get on up the road. So, I met up with a guy they called Ben. He was a good singer, man. We hoboed from Atlanta, Georgia, to Baltimore, started messing around, got us some odd jobs, and started playing in some clubs and things. The first band I got with was with Lightnin’ Hopkins. We played Little Poodle Dog, Get My Airplane, and all of that. I got with him when I was on the road. I was with him off and on for about a year. There was just three of us with Lightnin’—a drummer and two guitars. Then I left and went to Tampa, Florida. I stayed in Tampa for about six months, then I went to Orlando and hooked up with Jimmy Straits’ Fair. They had a train. That is when they had jig shows. They had a band with women shaking their hips, dancing, a guy buck dancing, blackface, all that shit.

[We played] whatever they could dance by—Dixieland, jazz, show tunes, blues. There was a thing called the Midnight Ramble. It was after midnight. All the kids were put out of the tent, the price would be raised, and the dancers showed more, and that is when we would throw down with the blues. . . we would tear down on a Saturday night.

One of the guys came out one day and said, “Hey, Gabe. I said, “What? He said, “Gabriel, hell, that would be a good name for you. Well, I said, “Lay it on me, and so I have had it ever since.

All the carnies [carnival workers] they rode in the train. It was a regular train, but it was a show train. The only way to take a bath was in a tent or you had to go to the hotel. It was an outdoor life. There is no discrimination in show work. All carnies stick together, white or black. I was pulling down around $300 a week and all I could eat. I was just playing and having myself a ball. That was after the war [World War II]. I went over to Hawaii too, that was with Louis Jordan. He’s dead now. I went over there one time with him and did some shows playing in his band. I played rhythm guitar for Bo Diddley, for about four or five nights. See, along then I was on the road, I wasn’t still. I met him in St. Louis, Missouri, in a cafe sitting there drinking a malted milk and eating a pack of nabs. But I had my guitar. See, I didn’t carry no case. I had my guitar on my shoulder. Just the belt and the guitar, no case. He happened to spot me. I didn’t know who he was and he didn’t know who I was. So, we got to talking. You know a guitar draws attention anyway. You don’t have to play it, just have it, and somebody is going to ask you something. He said, “Can you play that thing? I said, “A little bit. He said, “What’s your name? I told him “Bobby Jones. He said, “Hit me a tune. So I plucked him off one. He said, “Are you working anywhere? I said no. He said, “Would you like to work with me tonight? I said okay. So he took me down to a place [and] he bought me a set of guitar strings. So, I strung it up. Sure enough, we made the gig and he gave me $100. So, he said, “Well, how long do you think you are going to be around here? I said, “I don’t know. I went down to a rooming house and got something to eat. I stayed around there a couple days and I got to drinking that damn sweet wine. I was drinking heavy back then. I said let me book on. Hot in the summertime, I never will forget, about 80 degrees. I got my guitar and I walked on uptown. I asked a wino, “Hey, man, which way is the railroad tracks. He said, “I will tell you what to do. You go up Lee Street and make a right and then turn a left and you will be right on the railroad tracks. He said, “You are figuring to put us down, huh? I said, “Yeah, move on down the line. I got a few hundred dollars in my pocket. I got on down to the tracks. The train came by and I wait until I see me a flat car. When it hit that hill I got me a flat car. I went to sleep. When it stopped, shit, we was in New Orleans. It stopped at the water tank. That what woke me up, hearing that water going in the train. I saw all those dicks, I said shit, I’d better get out on the other side. So I met up with this guy and I asked him where I was. He said, “Hell, you are in New Orleans. You don’t know where you are? I said, “Oh, I forgot. I said, “Look here, tell me where the blacks live down along this way. He told me to catch the bus number 15 and ride it and get off along Fox Road. “You will hear them and you will see them. There comes the old bus. I got on and rode ‘til I got off. Then I started walking slow. I stayed there a few years. I started going with a big fat girl named Margaret. Yeah, I used to have a good time. I used to love to hobo and travel. If I got in a town and I was doing good, I wouldn’t stay there for over a month.

I played rhythm guitar for this guy named King Curtis. He was a guitar player, he was almost like another Albert King. I played with Chuck Berry in New York, played with Lightnin’ Hopkins in Newark, New Jersey, and I played with Muddy Waters in New Orleans. I played with B. B. King in Dothan, Alabama. I have been with Jimmy Reed, we were in California, Oakland. I have been to the Apollo. . . and I did a show with T-Bone Walker, and on the package show there, there was another guy they called Big Boy Crudup. I met Blind Boy Fuller in Durham. That was years ago.

The greatest experience I had though, I was hitchhiking and a car stopped with a white lady in [an] old Buick. It looked good though, it was shiny. She stopped and said, “Where are you going mister? I said, “Can I get a lift Miss? I said, “My feets are sore. I said I wanted to get to the next town. She said, “Where are you going? I said, “Wherever I can get to. I said, “If I can get there I can make it. She said, “Get in, can you play that guitar? I said, “A little bit. She said, “Play me one. I hit a blues. I had a keen voice back then like a girl’s. She said, “Oooh, you are wonderful. So she carried me on to the next town. So, she stopped. She said, “If I wasn’t married I would go with you. I said, “Well? She said, “Look here, do you got any money? I said, “No, ma’am, I’m broke. “Here’s 15 dollars. You stop and get something to eat, hear? I said, “I will. “You take it easy. I said, “God bless you, sister, same to you. She pulled off. I got to town and I met me a wino. I didn’t know where anybody lived. I said, “Where does everyone hang out around here? He said “Follow me. Me and him started walking. He carried me around to a juke joint place. I messed around there for a couple months. I made myself about 400 or 500 dollars. So, I pulled out again and left. Started traveling some more. That has been my experience out of life, traveling up and down the road. I’ve had opportunities that back in them days a black man didn’t have. Because I was a musician. I had white women. A whole lot of black men never got to go with a white woman. They would get hung or killed. I’ve lived it. I left Winston-Salem and went to Pittsburgh. I started playing at the bars up there—the Big Apple, Two Spot, Chat and Chew. Some dudes run into me and they wanted to make some recordings. It sounded good to me because I hadn’t recorded. They took me down to the studio on Broad and Market in Pittsburgh. We got on down there. [Bill Lawrence, the producer] made up the name [Nyles Jones]. That is how I wound up with that. He said that [the] name would sell more records. I recorded the Poodle Dog, Welfare Blues, and I recorded some others. I made a 45 and an LP. My 45 was very popular. I didn’t get anything out of it. It took a lot out of me. I was looking for that guy who owned the record company, but I never did find him. They said he moved. Well, it just goes to show you what goes up must come down.

I got beat out of the money out of those recordings and I came back to Winston [-Salem] and I hung up my guitar for about a year. I started doing some construction and cutting grass. If I was feeling good I would go to a house party or play for a cook-out or something like that. I used to drive a crane, bulldozer. I did outside work. I love that work because that is the kind of work my daddy used to do.

Channel Two [WFMY-TV in Greensboro, North Carolina] came and put me on the news. I started playing and got some money and I went on a two weeks drunk. I messed up about $400. . . me and two color[ed] boys and two white girls. I went to a Food Fair and stole a jug of wine. I stole a pound of pork chops and a carton of cigarettes. I got caught in the store—one of those store walkers caught me. So, I took my elbow and hit him in the chest and before I could get out the door they done grabbed me and took me on to jail. I got out on my own recognizance. The next week was my trial date. I had on my white suit and my black shoes, white shirt, black tie, had my guitar on me. They called my name Robert Jones, alias Guitar Gabriel. “How do you plead? They got you down here for shoplifting in a grocery store. He said, “What do you have there? I said, “That’s my guitar. He said, “Can you play it? I said, “A little bit. He said, “Can you play Amazing Grace. I said yup. He said, “Play it for me. One white lady was back there with the rest of the people. She fainted. I knew I was free then. He looked at me and said, “Look here, you got too much talent to be doing what you’re doing. I told him about me being on the drunk and everything. He said, “I should keep you down here to entertain us, but I’m not going to do that this time. I’m going to let you go. So the rest of the guys, they picked me up like I was a star or something and took me on down to Fourth Street and made me drunk. The next morning I was in the Winston-[Salem] Journal, with my picture and my article.

Winston-Salem is a tobacco town and R. J. Reynolds, the old man, he employed a lot of people. It was a pretty good life. Wages was high, you could make a living and [the] dollar valued something. Which it doesn’t do anymore. I’ve seen the time when I was a boy—if you spent 40 dollars it would have taken a truck to get the groceries home. Now you can bring it home in a bag. That should show you what the difference is. Things have done changed, people done changed. Time doesn’t stand still, doesn’t wait for no one. Everyone is in a hurry going nowhere and that is about the size of it. Everyone is trying to get there but they don’t know where they are going. The first thing we have got to do is to unite with each other. Trust, respect, and have friendship. . . . Together we stand, divided we fall. There is no racism amongst children, it is taught by the grownups. You can put a little white child out there and a little black child out there. They can play together all day along. If the parents would stay out of it, it would be nice. But they don’t. On one side they are telling them about it and the other side they are too. When they grow up they are going to hate each other. You know why? Because they are brain washing the kid. They are not born prejudiced, they are taught. And that is the way life is going today. I remember when a black man couldn’t drink from the same water fountain, go to the same bathroom. I am so glad that things are changing but they have a long way to go. Martin Luther King and President Kennedy put things on the move.

There was a white church and there was a black church. I don’t know what color Jesus was but whatever color he was, the way they got him they got him all messed up. So, that’s life. You accept life for the way it is. We do not know what time we are going to pass this world. But what it is, we have to learn to unite together before we go.

So many people are out misusing, misrepresenting themselves with something that ain’t fun. Everybody doesn’t know their destination. Some are born to be a brick mason, a school teacher, but you got to find out what are your goals yourself. You got a whole lot of people out here that don’t know what they are qualified in doing. All [they] do is go to work, get his lunch bucket, and that is all they know. Because he is not trying to invest and learn anything else. You see that is life. The weak shall fall and the strong survive. Personal experience can trick you too. Everything you see that looks good ain’t good. It looks good, but eyesight will fool the hell out of you. That is where hoodoo’s tricks come in at. The hand is faster than the eye. You think you see but you don’t. That is the same as playing three card Molly, Catch the Greasy Pig, and all that. Eyesight will fool you. Life is a tricky thing, but it is nice. . . going nowhere and that is about the size of it. Everyone is trying to get there but they don’t know where they are going.

The first thing we have got to do is to unite with each other. Trust, respect, and have friendship. . . . Together we stand, divided we fall. There is no racism amongst children, it is taught by the grownups. You can put a little white child out there and a little black child out there. They can play together all day along. If the parents would stay out of it, it would be nice. But they don’t. On one side they are telling them about it and the other side they are too. When they grow up they are going to hate each other. You know why? Because they are brain washing the kid. They are not born prejudiced, they are taught. And that is the way life is going today. I remember when a black man couldn’t drink from the same water fountain, go to the same bathroom. I am so glad that things are changing but they have a long way to go. Martin Luther King and President Kennedy put things on the move.

There was a white church and there was a black church. I don’t know what color Jesus was but whatever color he was, the way they got him they got him all messed up. So, that’s life. You accept life for the way it is. We do not know what time we are going to pass this world. But what it is, we have to learn to unite together before we go.

So many people are out misusing, misrepresenting themselves with something that ain’t fun. Everybody doesn’t know their destination. Some are born to be a brick mason, a school teacher, but you got to find out what are your goals yourself. You got a whole lot of people out here that don’t know what they are qualified in doing. All [they] do is go to work, get his lunch bucket, and that is all they know. Because he is not trying to invest and learn anything else. You see that is life. The weak shall fall and the strong survive. Personal experience can trick you too. Everything you see that looks good ain’t good. It looks good, but eyesight will fool the hell out of you. That is where hoodoo’s tricks come in at. The hand is faster than the eye. You think you see but you don’t. That is the same as playing three card Molly, Catch the Greasy Pig, and all that. Eyesight will fool you. Life is a tricky thing, but it is nice. . . according to how you unite it and you arrange it and the way you want it to go, and you make your dreams and your fantasies come true. You see a lot of people start on it and quit, but if you want to accomplish a goal, you stay at it, it will come through. Like baseball players, fighters, basketball, hockey. You got a lot of white boys playing music just like black boys, singing like them, dancing like them, dressing like them. Used to be a white man dance, he jumped straight up and down like a chicken. He didn’t know how to dance. He picked up a lot of things from the black man.

When I make other people happy, then I am happy. About music—it keeps you out of violence. Blues is special because it takes a lot of animosity out of your heart. Like, if you have a misunderstanding. Instead of taking violence out with your fists, you take it out on your music. If you get disheartened you take the guitar and you can satisfy yourself and that takes all [the] evil thoughts away from you. That is what music is all about. That’s the bottom of it. When you can do that you are all right and you got something to fall back on. If you can’t play no music, sing, or dance, and all you can do is think, you got to do something to take that pressure off. If you drink that drink, [it] is going to make you violent and you have no choice because you have nothing else to turn to. You got to have an outlet. If you can get to the thing you love, it is going to take that evil heart away from you. That is about the bottom line on me.

Music is a difficult thing if you do not understand it. Music is a feeling. If you can’t feel what you are doing you can’t do it. If you don’t like what you are doing you are not going to do it. You can do it, but you won’t be good at it. Like a preacher. You take a city preacher, he’ll say, “Ladies and gentlemen. No one wants to hear that shit. You get one of those old country preachers—he will start screaming. He is doing it from his heart. See the main thing is reaching the audience. Make them feel what you feel. Once you do that you are all right. Other than that. . . you might as well hang it up.

I’m good but I don’t brag it. I am not afraid to get in front of anybody. I know I am good. When you know something you do not have to ask nobody. As long as I feel it in my heart that I am good, I am good. I have played so much guitar it could make your ass hurt.

Blues is something that you do not find in no notes. You don’t find it on paper. It is something which is in your heart. You got to feel it to do it. You got to experience it. If you live it you know what I’m talking about. Sometimes we can be happy, sometimes we can be blue. It’s only what life chooses for you. You can wake up in the morning going to your job, doing your daily occupation, 24 hours or eight hours. That’s the blues. When things don’t go right, seems like everything you do is wrong, that’s the blues. You can be in your home and have the blues. You can be on the train. You can get it too. That’s the blues. Or you can be in New York City with over 20 million people and have the blues, that’s what I’m talking about. That’s the blues. It explains your mishappenings, it explains your misfortunes, it explains your ups and downs, where you have been around. That’s the blues. That’s what life chooses, you know. Now blues ain’t nothing but a feeling. It’s either you have or you don’t. It is something that God gives you. Men can’t take it away. You know sometime we can be happy, sometime we can be blue, you go down to the wilderness you see little birds cheeping, they got it too. That’s the blues. . . . Back in Africa before my time, they use to take a paper sack and play the blues. Yeah. So to experience life, it will tell you all about that too. . .[My hat] is an African hat. And what it is, it brings the story about the culture that you have been through. The things that you have seen in life and the trouble that you have experienced, and the people that you have been around. So, it kind of gives you the flavor of the blues. . . so whenever you wear this hat, it gives you a feeling of what you are representing. Anything that you take on to do, got to have a basing to let people know what it is and what it stands for. You can drive a Cadillac but if it don’t got Cadillac on it and people don’t know what the car is, they still don’t know what it is you are driving. So, that is the same thing. That is the story behind that. Blues will never die because it is a spirit. It is an uplift and the way you feel it, that is the way it is. And it brings a lot of joy to people. Music is made to make happiness, make you smile and forget your troubles. In the Good Book it says to make a joyful noise. It doesn’t say what kind of noise, just as long as you make one. So that is about the size of it. That is what we are trying to do.

Guitar Gabriel’s story is taken from interviews conducted by Timothy Duffy. This article was first published in Living Blues no. 103.