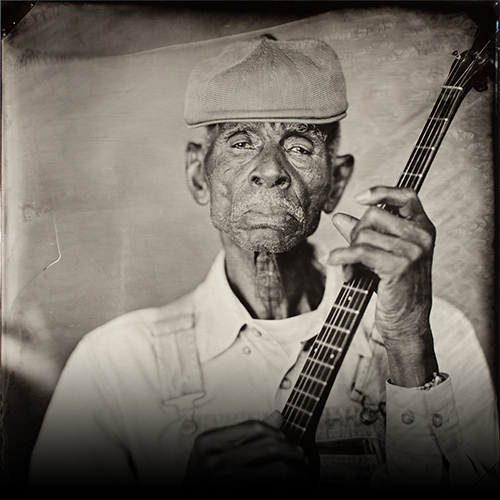

Biography

Eddie Tigner plays the piano with a smooth, strong base that rolls along below the weave of the soulful notes of the upper registers. He is a musician who can move an audience from the swing of Heartbreak – It’s hurtin’ me to the rocking sound of Shake Rattle and Roll. For Tigner, the piano is not just an instrument; it’s a place to be.

How We Helped:

Eddie Tigner joined the ranks of the Music Maker Relief Foundation’s artists in 1998. Music Maker has helped Eddie obtain a passport, provided him with grants for prescription medicine, and gifted him with a keyboard. In addition, Eddie has toured with the Music Maker Blues Revue throughout Europe and the United States, recorded his albums Route 66 and Slippin’ In, and been featured in the book Music Makers: Portraits and Songs from the Roots of America (2004) and the Music Maker documentary Toot Blues.

“You can’t separate the person and his music – especially with this man. When you are in his presence, you can’t help but smile. You can’t help but be happy and joyful and when he plays it’s the same thing. If you were blind and you heard him play, you would just be so joyful!” – Mudcat Dudeck

Eddie Tigner was born in Macon, Georgia in 1926. When his father was killed by mustard gas in WW I, Tigner’s mother married a coal miner and moved the family to Kentucky. She played piano at house-parties, breakdowns, fish fries, and barbeques, often with her kids in tow. “My mother played barrel house, boogey woogie in Kentucky,” Tigner remembers, “They’d be making sausage, or build a fire to roast pig and Mama and the guitar player would show up. They’d take an old raggedy piano and move it outside! It was kinda weird but it sounded good.”

Tigner laughs when he remembers his own response to music in Kentucky. His mother may have paved the way for his life as a piano player, but Tigner admits that, as a kid, “I wanted to play the guitar. I wanted to play bluegrass! But I never did get used to it. I tried it and I just couldn’t get my left hand right.”

It’s that spirit of play and resignation that has set the pace for Tigner all his life. When he enlisted in the military his familiarity with all kinds of music got him a special service assignment booking bands for the club on the base at Aberdeen. He took up the piano and got to know a lot of musicians. Folks like Les Paul were young enlisted men but, in the clubs and canteens, they also had time to play. In this company, Tigner developed his own eclectic style. After his discharge, he returned to Atlanta, joined the musicians union and, in addition to piano, Tigner took up vibes for awhile and played with a group called the Maroon Notes.

One of the most popular musical groups in the 1940’s was The Ink Spots. When the original bass player died in 1947, the agent, I.D. Kemp, got involved in organizing a number of “Ink Spot” bands. He had met Tigner booking bands for the clubs on U.S. bases. Kemp picked up on Tigner’s base-style of playing on the piano and put his name in for one of the groups. That led to a life on the road and a steady job as an “Ink Spot” that lasted until 1987. The band played in clubs and lounges in the new “motels”, the Holiday Inn or Ramada Inn, and stopped at military bases in every state.

Life on the road was hard, but Tigner likes to recall how he developed his own home-on-the-road routine. “I had me a crock pot,” Tigner explains, “and I would make me what I want. Gizzards and rice. I loved that back then. Put it on before I go downstairs to play and when I came back it be pretty well done!”

In addition to decades as an Ink Spot, Tigner traveled with vaudeville legend Snake Anthony. Tigner likes to tell a story about Snake’s shows at the Augusta Theater that speaks for the open edges of the world of music at the time. There was a 14 year old kid named James Brown who was always out in front of the theater shining shoes. “We would invite him on stage,” Tigner says, with a nod to the kid who rose to the top. “Snake didn’t care who you were if you had talent. And he [Brown] could dance! He was good. All that slide when he was only a kid!”

Working wth Snake and playing with the Ink Spots, touring across 48 states, Tigner got to know a lot of musicians and learned to weave his playing into a mess of groups. In Atlanta, he played a place called the Lithonia Country Club where he met Elmore James, T. Bone Walker and Gate Miles Brown. The club had a mixed race clientele that appreciated the blues, especially when it was drawn up for dancing.

As Tigner got older, the pace of the road bore down on him. Finally a heart attack sounded the alarm and pulled him off the road. Undaunted, he took a job in a school cafeteria but kept his piano-playing hand in the scene. He settled in Atlanta and became a regular at places like the Northside and Fat Matt’s Rib Shack, but, unlike bands who grabbed onto the blues revival, Tigner never cut a record. That is until one day at the turn of the millennium when his Chicken Shack bandmates, harmonica player Paul Linden, bassist Matt Sickles, and drummer Ron Logsdon, suggested the recording idea. “[They] asked me if I wanted to record, and I said, ‘I don’t care nothing about recording. I just play ‘cause I love to play.’ They said, ‘You’re 70-some years old. You should put something down so that if anything happens, you have something to leave behind.’ That’s how it got started.”

Through “Mudcat” Dudack, Tigner hooked up with the Music Maker Relief Foundation and the result was Route 66. As classic and cross-country as its namesake, the album shows off Tigner’s range. He plays standards, but ranges wide from his own version of Take the ‘A’ Train to Stormy Monday and C.C. Rider. The Chicken Shack players appear on the album along with tracks that feature Doug Jones on guitar, John Weiland on bass, and Steve Hawkins on drums. Tigner even takes up the organ on some of the cuts.

Touched by the recording bug and supported by Music Maker, Tigner recorded a second album, Slippin’ In, where he shows his hand as a song-writer in the title track. The songs spread out from swing and blues to novelty tracks like Did You Ever See A Monkey Play a Fiddle. The recordings have spread Tigner’s music around and they’ve taken him back on the road. He still favors his weekly gigs in Atlanta, but Tigner has added festivals to his road list including the Chicago Blues Festival, Blues to Bop Festival in Lugano, Switzerland, and a six week tour of Europe in 2010.

If it sounds like straight up, that’s just Tigner’s spirit beaming through. In 2010 his car was stolen along with a lot of his best equipment sitting in the trunk. “Someone stole my car,” Tigner says, a touch of disbelief in his voice. “They cleaned me out. I got my car back,” he adds with a wry laugh. “The police called and said ‘Mr. Tigner, I got your car’ and I said ‘it’s out in my driveway’ and he said ‘you better check!’ “

Music Maker and a lot of friends world-wide pitched in to help replace the lost equipment. Undaunted, Tigner says, “I got a whole bunch of stuff now. Someone sent me a microphone. Keyboard. All of my stuff.! Mudcat gave me an amp. I have really been blessed!”

That’s Tigner’s spirit. You see it at home and you see it on stage. Recently, Tigner noticed that he was forgetting things. He had to give up his job at the elementary school cafeteria where he was not just a service worker but the guy who could reach even the most recalcitrant kids. The official diagnosis is Alzheimer’s. “I asked doctor what that was,” Tigner caps off his story, “and she said, ‘Eddie if you don’t know. you’ll find out.’ I haven’t found out yet!” Tigner laughs. “I asked should I stop playing? ‘No,’ she said. ‘you just keep playing.’ I said. ‘but what if you forget from Alzheimer’s?’ She said, ‘Eddie you won’t forget your music.’ ”

And nobody who hears him will forget Eddie Tigner.